Melinda Schawel

As musicians, comedians, actors and painters can tell you, there are few things more difficult or more technically demanding than to be spontaneous on purpose. For many, if you can see the art in it, then the thing has already failed. Far better to be startled, just as the artist appears to be startled, by the accidentally perfect thing. All the better when it emerges, paradoxically, out of trained hands with years of practice.

As I clock up the years and my skills improve and perceptions deepen with use, I’ve come to more and more appreciate those things which seem to have simply occurred, and yet attain a kind of perfection which is often difficult to communicate to others not used to seeing it. It’s the kind of quality Chinese brush paintings can possess, or Japanese ceramics, or the painting of an artist like Antoni Tapies.

Last week, while in the city for some work related training, I had a few minutes to kill and wandered into the George Adams Gallery at the Arts Centre. It’s the kind of space that usually shows splashy travelling shows which are very light on the curatorial pedal, like the Archibald Prize; the sort of thing people who are there for a musical might be happy to kill some time in, until the curtain comes up.

They have a show presently called ‘Meeting Place, Keeping Place’, whose rationale is ‘Victoria’s cultural diversity and the vitality that different cultures bring to the visual and performing arts’. The participating artists are all émigrés from around the world who now call Australia home.

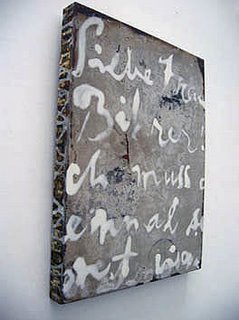

I was drawn immediately to work by Melinda Schawel, who I had never encountered before; a series of word paintings, dense and highly cultivated, abraded and heavy, worried into existence. The kind of stuff that really pushes my buttons, to be perfectly honest.

It was the kind of experience that’s exhilarating and also a bit embarrassing. When you have to say frankly, “I wish I’d done that”. I recognised immediately that these paintings had achieved the kind of artlessness that I was trying to get myself in the work I had completed last year for my own Masters degree show. Seeing these things, I became aware how little I had really achieved and how far there was still to go.

What was worse, the text which attended the works sounded like it could have been a quote from my own Exegesis. Damn it.

I was standing at the bus stop when an elderly woman approached and started chatting to me while I nodded and smiled in what I hoped were the right places. I waited for a lull in the chatter to say ‘es tut mir leid, ich spreche nur ein bisschen Deutsch’, but it never came. The bus arrived a few minutes later, so we bid each other a fond farewell. I boarded in a daze wondering how I could actually participate in an exchange without contributing or understanding a single word.

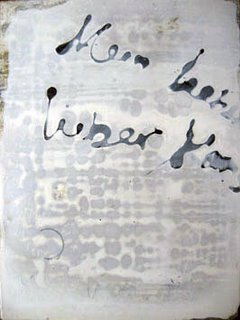

It was one of many one-sided conversations I had when I first arrived in Zürich in 2001. I wasn't an obvious foreigner; my father's roots are German and my mother's Slavic/Polish. Learning the language would be intrinsic to understanding the culture in which I was now immersed. The gaps or slippages that occur in communication, both between and within cultures, is the current focus of my work - what is misinterpreted, misunderstood or simply left unsaid.

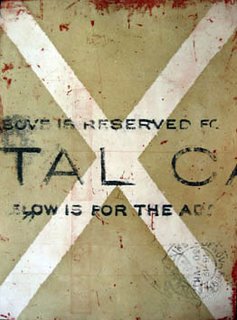

My latest works are based on excerpts from antique letters and postcards found at the second hand shop in Zürich. They initially appealed to me because of the time that was invested to sustain and nurture personal relationships through the ritual of putting pen to paper. In contrast to the brief exchange at the bus stop, the handwritten correspondence also allowed me time to absorb intimate information about the lives of the writers. I decided to use these carefully constructed foreign scripts in an attempt to create a visual language of my own, one that might serve as a bridge across cultures when words alone cannot.

I was genuinely excited to find that Melinda had her own website, which is extremely simple and quite beautiful.

The works, both prints and paintings, are worked up in dense layers, mimicking the surfaces that life creates by accident, scuffed, grazed, and populated with a private language of signs and symbols. The kind that bump up against each other in overlapping semiological codes, whose explicit meaning might be just beyond us, but which act upon our senses in emotionally loaded if allusive ways.

Fragments of handwriting in old cursive script overlap sequences of apparently random numbers, stamps, symbols and markers, against a surface of tobacco coloured writing paper; letters containing we don’t know what longing for love or home. The associations are clear and we make the emotional inference.

The objects themselves seem to have simply come about through use, containing merely the marks which life leaves behind. The exquisitely difficult art of artlessness.

I’m excited to see that she has an exhibition coming soon at Flinders Lane Gallery, from September 5 to 23. I’m glad that she shares a home with Terri Brooks, an artist also capable of the same achievement. I’ll be there, and I might even introduce myself.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment