This is shamelessly self-serving, but an extremely interesting exhibition will open soon at Lab X Gallery in St Kilda, entitled 'Phantasm'.

It's self-serving not because I am in it - I'm not - but I have written the catalogue introduction at the invitation of the exhibitors who I have known for many years. Greg Wayn and Greg Neville had the dubious pleasure of teaching me, and George Alamidis was also strongly associated with the school where I studied photography, ACPAC, whose star burned brightly in Melbourne for a few years in the eighties and nineties.

The theme of the show is the human face - not as it is in itself, nor as conventionally reflected in portraiture, but as it occupies the mind, whether in memory, in hallucination, or in the darker spaces of consciousness. The faces in 'Phantasm' bridge the apparent contradiction between our belief in the dependibility of faces on the one hand, and the more fragile residence they may take up in recollection.

Update: The website for the show is no longer operational, so in lieu, here is the text, for posteriy's sake, of the catalogue introduction:

PHANTASM

There is a strange double aspect to the human face. On the one hand, it is the most certain, the most concrete of visual forms; a form to which our brains give priority above all others.

Indeed, we seem to have an innate ability to recognise faces, since the face is a form to which infants only nine minutes old, who have never seen one, give special attention [Goren, 1975]. Brain imaging studies show heightened activity in an area of the temporal lobe called the fusiform gyrus when we look at faces, a feature of brain function that is evident by two months of age [Nelson, 2001].

On the other hand, faces have a fragile residence in the mind. The longer we consider them, especially in memory, the less substantial they become. Despite the assumptions of the criminal law, eyewitnesses often prove unreliable, so willing are we to confabulate past experience through the filters of desire and unconscious motivation.

Faces are like this, simultaneously concrete and yet often at the edge of perception and account, for which we struggle to find appropriate metaphor.

The faces in Phantasm bridge this apparent contradiction, appearing not as they are in themselves (whatever that might be), but as they occupy the mind, whether in consciousness, in memory, in hallucination, or in the dark places.

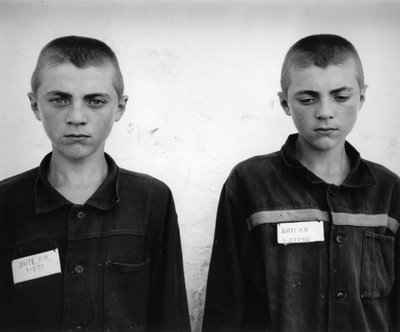

Greg Neville’s faces can be categorised by simple emotions: angry, happy, surprised, frightened; like characters from children’s books, with emotions more powerful for their simplicity. Looming out of a psychically impenetrable murk, radically simplified like tribal masks, whose animistic and magical qualities they suggest, his images emerge out of a longheld interest in collective and institutional images of identity, in this case, children’s toys possessing hyper-inflated masculinity.

Toys are a societal spirit-level, and often reflect our most obscure motivations in extreme form; never more so than when toys are overtly gendered. Like miniaturised classical statuary, absurdly stylised renditions of terrible physical power, they manifest the fears and desires of society in cheap plastic, a society seemingly obsessed with physical force even on the international stage. By simplifying masculine images for children, we universalise and distil and refine what was unnameable before, reflecting ourselves back in caricature. An artifact of public spectacle is here transformed by an accident of digital photographic process into an image from a private nightmare, and presented back to us as an entirely different kind of spectacle.

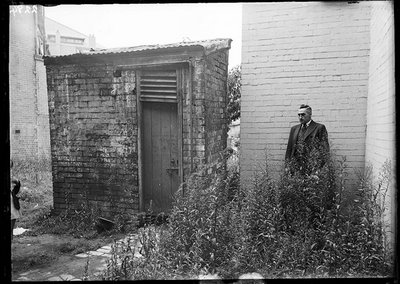

The brain sees a mouth and eyes where there is only a line with two circles. We are face-builders, neurologically set for the task. We come into the world seemingly knowing what faces look like, prepared to see them in everything from the moon to cheese sandwiches that look like Jesus. Greg Wayn sees faces where none exist. His pictures operate just above the neurological threshold for facial recognition, lighting up the inanimate world with consciousness. We see eyes where there are holes, mouths in smiling bedsprings, broken skin in the peeling paint of a car’s fender. We look, and a seemingly conscious object, animus mundi, stares back. We attribute agency and fellow feeling to junk, not simply because we are superstitious, but because we emerge ready to attribute mind to whatever looks like it has one, which is perhaps the source of empathy. In the rot and the rust, everything is alive, looking back at us, animated by our willingness to recognise it.

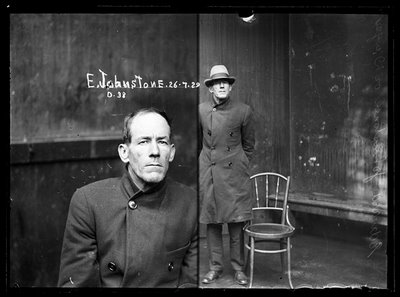

George Alamidis strips his faces of their institutional particulars, the singularity that underpins their uniqueness. They become universal, subverting the sole condition of their usefulness to institutions, governments and tyrants.

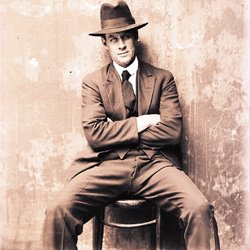

I say ‘his faces’ because they are all George’s face at some remove, having their origin in his elaborate self-portrait project; a portrait of the artist as an immigrant, a transgressor of institutional boundaries, whether of national and cultural borders, age, gender, class. A universal humanising gesture, which soaks up to the surface of an official document as if from some psychic depth. These faces are vessels, transistors of memory and common cultural experience, and vessels too because they come to us from the across the ocean, the universal boundary and the symbol of the loss of home.

Like no other object, faces indicate the contents of the soul and character. They guide us and shape our futures. They are showcases for the self, containers of social and sexual data which we recognise in the fraction of a second, the most important thing in our embodied universe. No wonder they haunt us.

We have only to consider the face of someone we have lost to become aware of the face’s double aspect. It seems simple enough at first, the image rising up in us with reassuring familiarity, as if they were still here, until we try to name the particulars: the shape and colour of the eyes, the angle of a chin, the distinctive slope of a nose. A whole album of sense memory can be within easy reach, smells, the sound of a voice, but the specifics hover in front of us like a name we can’t quite remember until we almost doubt that we ever knew them at all. The harder we look, the faster the remembered face atomises and fades away. We calm ourselves with the certainty of photographs until the face comes again, effortlessly, in dreams.

For the poet Ezra Pound, the memory of faces emerging from a Metro station was like an apparition, a ghostly image from the unconscious, “petals on a wet, black bough” [Pound, 1972]. There is no more symbolically potent, metaphorically fertile or more infinitely possible thing for us than a face conjured in the mind.

References

Goren, Sarty & Wu (1975) Visual following and pattern discrimination of face-like stimuli by newborn infants, Pediatrics, v. 40, no. 4, p. 547.

Nelson, C. A. (2001) The development and neural bases of face recognition, Infant and Child Development, 10. p. 3-18

Pound, Ezra (1972) In a Station of the Metro, Imagist Poetry, ed. Peter Jones. London: Penguin Books, p. 95.

.jpg)