'The Proposition'

Talk about a ‘black armband view of history’! Last night I was lucky enough to catch a screening of the new Australian film ‘The Proposition’ at Parliament House in Canberra, where it was introduced by the Minister for the Arts Rod Kemp. I noticed he made it to the end, but I can’t imagine him entertaining John and Janette Howard with anecdotes from the film around the dinner table at The Lodge any time soon.

To say this film paints a dark picture of Australia’s past is something of an understatement.

‘The Proposition’ is the second collaboration between director John Hillcoat and Nick Cave, after Cave co-wrote and acted in ‘Ghosts… of the Civil Dead’ (1988), which I haven’t seen. It was his involvement that got me to the screening. I can’t say I’m a member of the Cave cult, but I’ve admired him from afar ever since I was taken by a friend to see him play in Melbourne in 1990, which is still one of the best live performances by a band I’ve ever seen.

His pervasive sense of ‘Australian Gothic’ completely permeates this film from the opening frames, where the action is put into context by a montage of Victorian photographs of dear departed in decorated coffins, strung-up bushrangers and chained aborigines.

The film is a sort of art-Western in the tradition of Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah. It shares with Leone’s spaghetti westerns a dramatic sense of infinite space and a very black view of human nature, and shares Peckinpah’s cathartic violence. It’s a pity though, that it doesn’t have Leone’s leavening sense of humour and the grotesque. In fact, I think its relentlessness and lack of any sense of redemption is a problem, at least it was for me.

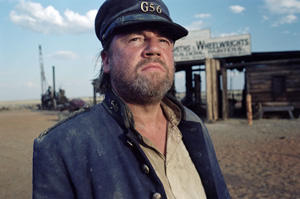

It’s set in western Queensland during the 1880s, in a landscape which is as brutal and scoured as any of the desperate characters. Guy Pearce stars as Charlie Burns, one of three brothers that make up the infamous Burns gang. Charlie and younger brother Mikey are captured after a stunning and vicious shoot out in an outback brothel with trooper Captain Stanley (Ray Winstone).

Stanley is after the psychopathic eldest brother Arthur and offers Charlie a proposition in order to bring the wanted man in. It is nine days until Christmas. Stanley will take Mikey into custody and he will be executed on Christmas day unless Charlie can hunt down and kill his older brother Arthur. Charlie must choose between his younger or older brothers.

When I say the film is bleak, I’m saying it has an unsparing view of human nature that is almost unrelieved. Every character is morally compromised, even Captain Stanley, who we come to respect, despite the fact that he casually sends out a group of troopers to round up and kill a group of ‘renegade blacks’ who turn out to be mostly women and children. I’ve read enough Australian history to know that this rendition of frontier justice is entirely accurate.

The language is spare but beautiful, especially in the early scenes, and the performances are uniformly superb. Winstone is brilliant, as usual, and I loved John Hurt’s revolting bounty hunter, who comes on like a character from Joseph Conrad gone mad from the heat.

Probably the very best thing about it is the image of a transplanted Anglo rectitude in a violently incongruous setting; roses, Christmas turkey, tea-time and all. “I will civilize this place”, Ray Winstone’s character says a couple of times, and we know his colonial arrogance will come apart at the seams. A particularly poignant scene occurs when Captain Stanley relieves his aboriginal gardener of his duties when he hears the Burns Gang are on their way. The gardener simply drops his spade, removes his shoes, opens the garden gate and goes back out into the desert wilderness.

My feeling about the film is that it suffers from a lack of resolution. In a Hollywood movie, we would expect to have our questions answered about the circumstances that lead to the brutal murder that occurs before the beginning of the action. Instead, Cave prefers to leave us hanging, to get us asking questions for ourselves about the characters and their previous deeds. The trouble is that the setting is so thin, the information so scarce, that it tends to have the opposite effect. I knew so little about Guy Pearce’s conflicted character that I found it difficult to get really interested in his plight. He’s like a hole in the middle of the film, his motivations not detailed enough to get us interested, so he simply functions as a catalyst for the actions of those around him.

Going out, I had a sense of emptiness, the pointlessness of the lives depicted here infecting the movie itself. I feel that there’s often something vaguely adolescent about Nick Cave’s murder ballads, all that unrelieved darkness and morbidity. I mean it works and it’s very rock and roll, and he obviously has a singular personality as a performer, but it’s not much to construct an aesthetic on. I have the same feeling about his film. The language and the images are beautiful and undeniably powerful, but I feel it has an emptiness at the heart of it.

.jpg)

2 comments:

Very interested to read it, thanks! You certainly churned it out quickly, you're an excellent writer Sean.

I still think there is redemption and resolution for Guy Pearce's character at the end in the choice he makes to kill his brother and stop the rape/murder that was taking place

Hmmm, think I have to see this one..some else mentioned it ages ago..they had seen the "shorts" (I think is the term used by people in the trade, he is a lighting techie)I was told it was parallel in the dark side of human nature to the old "Chant Of Jimmy Blacksmith". Which despite being courted as a horror flick by mainstream producers was a piece of great literature and historically accurate also. I had forgotten all about this film until you bought it up again,thanks.

Post a Comment