City of Shadows

A couple of years ago, Greg Neville and I went along to the forbidding sandstone buildings off Circular Quay which were the Sydney law courts, Water Police and lock-up cells from the 1850s. It is now the Justice and Police Museum and I found it absolutely fascinating; one of those experiences that burn into the visual memory and you can never quite shake it off.

At the time, there was a large exhibition of Police forensic and crime scene photographs from the early 20th Century. I forget the name of the exhibition, but it had that flash-blown, grimy quality that real images of this kind can have, but without the artistic ambition of a Weegee, which made it strangely even more powerful. The pictures had that profound weirdness that utilitarian or amateur photos can have when their context is stripped away.

The photographs were part of a very large archive of long-forgotten forensic negatives that were discovered in the late 1980s, but which had only begun to be looked at and catalogued years later. The project is still not complete. Unfortunately (or not, depending on your point of view), the paper records that accompanied the pictures were lost in a flood many years ago, and most of the faces, events and places have only been identified by painstaking comparison with the scandal sheet newspapers of the day and Police Gazette. Most of the pictures remain unidentified, which only increases their peculiar power and mystery.

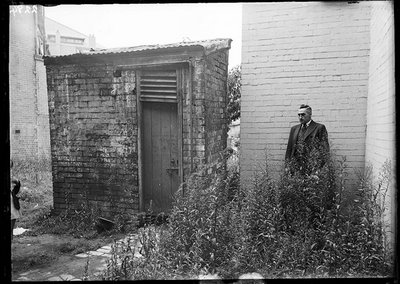

This, for example, is pure Surrealism:

The current exhibition, called City of Shadows: Inner City Crime & Mayhem 1912-1948, is almost as ambitious as the first one I saw and just as powerful. The only barrier for me was that this is not my city and so I didn’t have that immediate shock of recognising familiar places in an unfamiliar time.

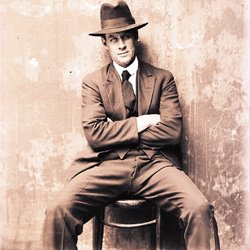

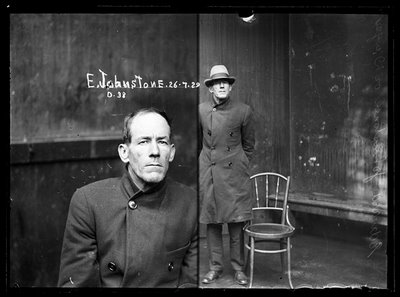

The most striking part of the show for me is the collection of mugshots, taken across the whole period in question. When I say mugshots, I simply mean images of arrested persons brought in to the city Police Station. In this period, it was only prison inductees who were photographed in the familiar front and side-on poses beloved of correction officials the world over.

People brought in and charged with various offences were simply asked to stand or sit in the natural light of the watch-house yard. Fortunately for us, the light was beautiful. Most of the time, they were not even asked to remove their hats. Many were just shot were they stood in a half frame exposure, with the other half sometimes taken with a close-up of the face. These pictures might be unique in the world. Certainly I’ve never seen anything like them before.

The selection of images here, painstakingly collected by crime writer Peter Doyle, display all of the emotion expressed (deliberately or not) by people in these circumstances. Some are frankly fearful, some resentful or outraged, some smile boastfully, some look like they would cut your throat rather than have to ask you for a light.

I bought the catalogue, City of Shadows: Sydney Police Photographs 1912-1948, which is an excellent distillation of the exhibition together with incisive essays by Peter Doyle and academic Caleb Williams. I spent the four hour train ride from Sydney to Canberra absolutely transfixed by this book, trying to read it without outraging my fellow passengers with the scenes of casual murder and mayhem spread across its pages.

Audio files can be accessed here, as well as more photographs from the show.

.jpg)

1 comment:

Sean, these are great -- thank you for sharing them. Do you know Luc Sante's stuff?

Post a Comment