Giacometti at the AGNSW

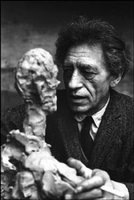

Imagine my excitement when I heard that the Art Gallery of New South Wales, only 712.35 kilometres away, was about to present the only major exhibition of Alberto Giacometti’s work ever held in this country. Earlier this year I travelled to Zurich, a distance of 16,333.77 kilometres to see the Giacometti collection, which gives you an idea how much the monkish Swiss artist means to me.

I have done a lot of work on Giacometti over the years, to postgraduate level, and attempting to understand his insights into the phenomenology of perception, especially with regards to drawing the human figure, has inspired me and inspires me still. So I did have high expectations of the show in Sydney, and I have to admit that they were only partially fulfilled.

I really should have known something was a bit crook when the curator Edmund Capon was opinionising before the opening of the show in various papers:

"I've always had this feeling about the graphics and the sculptures being completely harmonious and the paintings being a kind of parallel journey. I had a feeling that the wonderful austerity - the rich austerity - of the sculptures and the graphics might be disturbed by the paintings."

This should give any reader the idea that he does know what he’s talking about. Disturbed by the paintings? As anyone who has ever seen a Giacometti painting would know, they are merely extensions and elaborations of the theoretical concerns he explored in all his work, especially in the drawings and graphics, but in the sculptures as well.

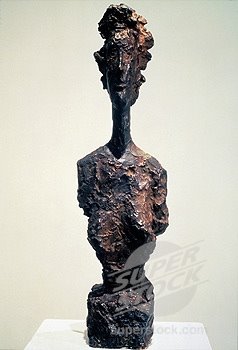

The agitated, pullulating surfaces of the late sculptures are physical manifestations of the idea that the figure confronting the artist (engaged in rendering what Giacometti called a “likeness”), is fundamentally unknowable, a phenomenological appearance without certain boundaries. This is what he meant when he was describing what occurred when his brother Diego sat for him: "He's posed for me ten thousand times. When he poses I no longer recognize him."

This understanding is the foundation of his drawing style, with its constantly searching, interrogating line. The presupposition of a drawing or painting by Giacometti is not “This is what I see”, but “Is this what I see?”

This was not adopted deliberately, but arrived at over a great deal of time, the essential product of his exploratory attitude to perceiving. Similarly, the faces in the figure paintings emerge out of an agitated architecture of gestural marks, which are the exact corollary of the pencil or etched line in the drawings.

Capon has also complained about the lack of recognition Giacometti has received in this country, almost alone among the twentieth century masters. He’s right, so it is precisely the paintings that we need to see.

This appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald:

“Capon, who has curated the show himself, explains why he hasn't included any of Giacometti's paintings. “You put one of his spindly, emasculated figures into a room and suddenly it defines the space," he says. "The drawings do that, too, but the paintings don't. I'm probably completely alone in thinking that, but that's OK."

Yes, I think you are Edmund.

This essential misunderstanding has left its mark on the show in other ways. The inclusion of several large standing figures, both male and female, and the prominent place they have been given is unfortunate, as these are some of the weakest works Giacometti ever completed. The reason is related to their theoretical underpinning, or lack of one. Several of them were done as commissions to furnish architechtural spaces and they are larger than life-size. The figures had to be that big in order to register within the dimensions of the outdoor space they would occupy. Unfortunately, this also undermined their reason for existing in the first place, which was as a record of a specific perception of a figure in space, its relation to the space around it and its distance from the perceiver.

This is why many of the other figures are so small, and why they perch from various stands, plinths, steles, and so on. The platforms serve as distancing devices, their angled edges often mimicking the abstraction of perspective lines, indicating distance. The scale of a tiny figure balanced atop a massive broze platform is to approximate the sensation of beholding a figure from a distance, say, from across the street.

The large figures in the show don’t function like this. Your eyes (the artist’s eyes) don’t have the same relationship to the sculpture, with the result that they look mannered, their stylistic conventions forced. When the figures are larger than life-size, your eye-lines no longer match and the sense of perspective, as the space rushes away the further from the eye you get, is lost. The experience is therefore secondary, like the reproduction of a painting compared with the original.

It was also probably a waste of time to include the surrealist period sculptures, since this era is so rich and complex, that to have a few of the greatest hits belittles their importance to the history of surrealism and sells the artist short. Why not simply concentrate on the 1940s to the 60s, since this is where the show’s heart obviously is?

I was excited to be able to see all of the ‘Women of Venice’ reunited. The gallery has owned one for some time, but to my knowledge, I’ve never seen them all lined up together, like whores on parade, which is what they are.

‘Study of Apples’ (1952) – unmistakeably the son of Cezanne. They reveal a sculptor’s preoccupation with structure.

‘Standing Nude’ (1960) – a delicate pencil drawing. A female figure, like an apparition.

The various studies of rooms in pencil. These are images of the house of his mother and father, in Stampa, Switzerland. Heavy, rustic furniture. His mother sewing. Domestic objects never to be found in his studio, which was more like a monk’s cell. These drawings always look like a breath of fresh mountain air to me. It has always been my impression that on these trips back home, Giacometti took his bearings, spent some time in a caring, supportive domestic environment, re-energising his art in the process. It seems to me that his art always made real progress during, or just after, trips home. An eraser cuts through the line, like shafts of light falling on the tables, the heavy chandelier. Time slowed down. The products of intense scrutinising.

“Bust of a Man” (1950), “Head of Diego with Rolled Collar” (1951-52), “Bust of Diego” (1954), “Bust of a Woman [Diane Bataille]” (1945) – Surely nothing is as familiar as the human face, and yet here it is as if seen for the first time. Raw phenomena, nothing but an open confrontation with the living subject, an exchange, in the knowledge of impending death. I think of his friend Beckett’s lines: “I can't go on. I'll go on.”

.jpg)

1 comment:

Fasinating,compelling yet very very raw. Funny how the curator felt the need to make such comments about the work.

Post a Comment